|

MADE FOR TV: A

WORLD-RECORD MARLIN**

Somewhere in the Western Pacific, I’d just filmed Cameron shooting a football-sized yellowfin tuna. I was watching the fish vibrate furiously as it was pulled to the surface when I heard Derek yell, "Marlin!" Instantly, I dove into a school of fleeing bait that was quickly contracting into a tight ball. The source of the bait’s fear—a gorgeous lit-up blue marlin—whacked its bill back and forth as it charged though the frenzied bait. What luck! All of the action took place within feet of the lens of my new high-definition camera and underwater housing, purchased specifically for the Outdoor Channel’s new spearfishing series Speargun Hunters. Weeks earlier, Cameron (Doggie) Kirkconnell traveled through Los Angeles where he triumphantly entered the US from Indonesia sporting his new dog tooth tuna world record. Cameron is a true man of the sea. He spends 6 months out of the year on the ocean as a merchant marine ship’s officer. He spends the other half of the year spearing fish at the far reaches of the globe. Judging that Cam would make a valuable team member for the TV series, I urged Cam to meet the show’s producer, and spearo himself, Robin Berg. The two hit it off. When Cam called a few weeks later offering an over-the-top inauguration location for the show, Robin agreed. With a week’s notice, Derek Stavenger from San Francisco agreed to join us as the third member of our team, for what became a world-record breaking trip. The high-definition camera promised to yield some fantastic images. With a camera on

loan from the Outdoor Channel, I used my lap pool to dial in the housing for color, focus

and depth-of-field. I was happy to find that the unit worked well in most automatic

modes—something extremely important in the fast-paced blue water environment.

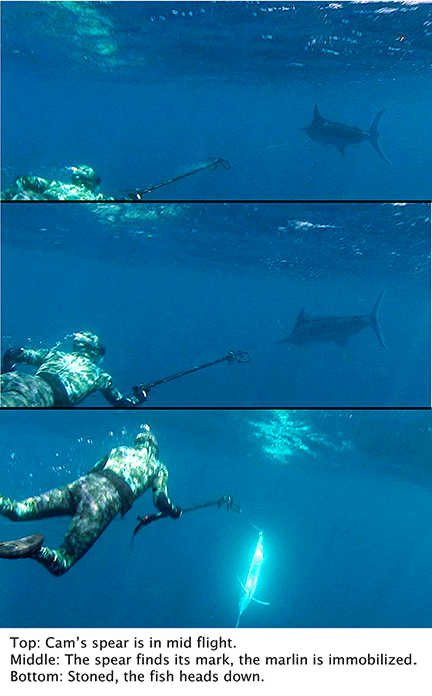

We planned to work as a team. I’d man the camera while Cam and Derek alternated between the positions of "shooter" and "shotgun." On the surface, I swam in tandem with the shooter while the back-up diver trailed several feet behind. The shotgun diver remained on the surface and watched for potential problems—sharks, boats, line and other potential hazards. If the shooter missed a shot, I often stayed below and trained the lens on the backup diver who might chase down a wounded fish or find another. It takes practice to work with a cameraman. In most cases, the camera needs to be abreast of, or slightly ahead of, the shooter. As we dove together, I would slip into the shooter’s wake in wing-man style. We hoped our two bodies would visually fuse in the eyes of our prey thus allowing a closer approach. The cameraman often continues to move forward while the shooter lines up. We made some great shots on mahi-mahi this way. The rub is that a perfectly executed shot looks too easy to the uninformed viewer. After a few dives with Cam, it was clear that he was national champion material. Cam was so quick that he often nailed a fish before I could press the record button. We regrouped on the surface and modified our approach. We agreed that Cam must wait for the camera before taking the shot; otherwise, we’d end up with a boat load of fish and no film. After this, Cam started making "warning shots." It seems he can hit the bull’s eye in 10-seconds but when he has 30 seconds to aim, he misses. Fortunately, the near-misses lent some credibility to our presentation by removing the appearance of "shooting fish in a barrel." We discovered that the best teamwork was directed by the shooter. To refine our approach, Cam placed a guiding hand on my upper arm. Like the dancer’s lead, he controlled the direction and the speed of our hunting pattern. He concentrated on looking forward and to the side opposite me while I covered my side. When he spotted a fish, he’d squeeze my arm signaling a dive. Alternatively, when I spotted a fish in my quadrant, I’d pull from his grasp, which alerted him to quarry and the need to dive. Diving with the large camera presented a challenge. Guiding it was like towing a 2-gallon bucket through the water. Furthermore, it’s nearly impossible to inhale a full lungful of air while simultaneously making a surface dive and keeping the shooter centered in the frame. On marlin day, we were hunting near a F.A.D. provided and maintained by the local community. The structure, occupying the area of a 3-car garage, was anchored in about 3,000 feet of water, 18-miles from shore. A large pipe stem protruded from the 20-foot diameter flotation drum, which connected to a radiating spoke structure 30 feet below. The spokes were connected by a 2-foot diameter stainless-steel pipe, wheel-like structure. Both the stem and the spoke wheel were encrusted with coral and supported an entire ecosystem. Predators lurked at the edges of the mixed-bait schools which layered themselves in an up-current orientation. Two Japanese blue water hunters, who knew of us through my book BlueWater Hunting and Freediving, allowed us to join them on their chartered boat, and further, graciously agreed to let us film a few passes by the F.A.D. before they entered the water. After Derek yelled, "Marlin!" their eyes became riveted on the hunt, which unfolded literally at their feet.

When I surfaced after filming the charging marlin, it retreated on the surface with me

in hot pursuit; chasing its massive and gradually disappearing tail. Meanwhile, Cam

stuffed the football tuna into his belt and re-loaded. On the boat, the captain and

Japanese divers were hopping up and down crying, "Marlin, Marlin!" As the marlin tightened its arc to almost 90-degrees left, I picked up Cameron in my peripheral vision. Guessing the fish’s trajectory, Cam dove with his two-banded, Euro-gun outstretched. Keeping both centered in the frame, I swam as fast as I could. Suddenly, the marlin flashed and rolled on its side—clearly mortally injured. On the surface, pandemonium had broken out on the Japanese fishing boat carrying our new found comrades. They had also seen the reflective flash and understood its significance. Cam’s aim was perfect, which allowed his fast-moving, small-diameter, single-barbed shaft to take down the giant.

|

||

| The fish sunk to about 60 feet. When Cam gingerly retrieved

his float line, Derek unloaded his gun so that Cam might use it for his second shot. When

the fish was raised to 30 feet, Cam deftly tied off the line and loaded Derek’s gun.

His second shot was perfectly placed in the spine behind the gills, and not a minute too

early as his first shaft slipped free. Within minutes, we’d boated the potential

record. Later at the docks, the accommodating captain and local support divers arranged

for a crane to pull the fish from its ice hold, a van to transport it to the weighing

facility and a certified scale for an accurate weighing. What an auspicious send off for our new show! Some may call Cam’s shot lucky. After following him around for several days, I can say that it was raw skill that allowed Cameron to take this record. The small tuna he shot, vibrating like roller skates on a washboard, probably attracted and excited the marlin. I subscribe to the definition of luck as the meeting of opportunity and preparedness—Cam had both. Want to find out where we dove in the Western Pacific? Stay tuned for SPEARGUN

HUNTERS on the Outdoor Channel and we’ll show you. |

SPEARGUN HUNTERS—A SPEARFISHING SERIES ON THE OUTDOOR CHANNEL This new TV series featuring spearfishing is the brain child of diver

and producer Robin Berg who currently produces three shows for the Outdoor Channel. Robin

is an ex-US Navy deep sea diver and has been spearfishing since the age of 9. He has been

producing television shows for 17 years. In a very short time, Robin assembled a

top-flight team of respected spearos representing the Our vision is to produce the best shows possible. Spearfishing will

be cast in the conservative light in which most of us practice the sport. Each show will

be unique and unpredictable. Besides pure hunting scenes, we’ll take some interesting

diversions. We will discuss the natural history of our game, general oceanic ecology, and

our place in that system. We’ll spend time explaining our specialized gear and

freediving and spearfishing techniques. Parts of the series will be devoted to historical

spearfishing personalities who will provide their own views of the sport and how it has

evolved. We will cover many of the popular spearfishing contests as well as spearfishing

clubs, for example, the Long Beach Neptunes and the Fathomiers. Currently, we have identified a potential team of international

contributors. From the West Coast we have, national champion Bill Ernst, cameraman Ron

Mullins, Derek Stavenger and David Laird. Multiple world record holders Cameron

Kirkconnell, Sheri Daye and Mark Labocetta will join Sasa Bratic and Chris Gardinal to

represent the East Coast while Mike McGuire will cover inland fishing. Daryl Wong and

Sterling Kaya will head up the Production of the series is already underway. Our first broadcast will be a one-hour special scheduled for September of this year followed by 13 shows beginning in January. |

||