|

Copyright © 2005 Terry Maas, BlueWater Freedivers |

||

(Enlarge) |

|||

| BLACK SEABASS RETURN ? By Terry Maas and Michael Domeier PhD. |

|||

| "Wow! "This is weird," I thought as I swam shoulder-to-shoulder with a 300-pound black seabass (bsb) on one side and nationally-recognized bsb expert Dr. Michael Domeier Phd. on the other. A half-hour after the sun set over Anacapa Island, I could see just 10 feet through the 60-foot visibility water. The unfamiliar rhythmic sound of my aqualung bubbles punctuated the gathering darkness. Occasionally, lightning flashes brightened the inky water as Mike's strobe blasted the 50 unconcerned gentle giants while they gathered—presumably to breed. As is the case with other oceanic fishes, we have more questions than answers about the natural history of bsb. Mike, with generous funding from avid angler and spearo Tom Pfleger, has answered many of our basic questions. Later in this article, Dr. Domeier explains his findings after 5 years of intensely studying these wonderful species. While Mike has witnessed captured bsb spawning, he has not yet seen this event in the natural environment. We chose dusk during a brisk current in September—the historical date when the largest aggregations appear—to study the behavior of this particular school. We selected this time because similar species use dusk and currents to allow their fertilized eggs to disburse before local bait fish decimate the spawn. |

|

||

Three years ago, local

divers shared with me their secret location where they found a large school of bsb. For

the next several weeks, while the water remained clear, I freedove with over 50 fish

ranging in size from 100- to 300-pounds. Unlike other bsb gathering locations, this reef

contains no kelp. Instead of orienting with the kelp as a kind of signpost, these fish

swim unfettered over the rocky bottom and often suspended high in the water column. As

with other schools of bsb, it is possible to approach to within a few feet of these

aquatic Volkswagens as they range over the sand and rock bottom, while they orient their

direction into the oncoming current. Several years ago, I first met Dr. Domeier at a scientific conference

on the monitoring of the newly created Mike

has a passion for the sea and its fishes. He has studied bsb extensively. Mike spearheaded

the study of bsb movements with an impressive array of underwater acoustical receivers,

which record movements of fish implanted with special transponders. He’s examined the

fish’s stomach contents and trawled for juvenile fish off the |

|

||

Mike agreed that this particular aggregation on |

|

||

When I started diving in Here’s what Mike has to say: |

|||

My roots as a marine biologist are anchored firmly in

coral reef fish ecology. That goes a long way

towards explaining my immediate draw to giant sea bass (locally called black seabass in Both

goliath grouper and giant sea bass get very large, have lifespans about as long as humans

and reproduce at a relatively modest rate compared to other fish species. Furthermore, both species aggregate at specific

times of the year, presumably to spawn. All of

the above characteristics make these fishes very vulnerable to overfishing since they can

easily be removed quicker than they can reproduce. Their

large size and approachable manor made them an easy trophy for spearfishermen and it is

very likely that these are two rare examples where spearfishing had a negative impact on a

fish population. Once an aggregation site was

located it could be hammered year after year until the fish were gone. The

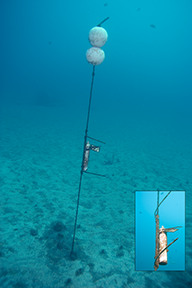

1990’s saw the advent of some revolutionary types of electronic fish tags that

allowed researchers to track and monitor individual fish movements. Both acoustic tags and satellite popup tags were

suddenly responsible for unraveling mysteries about fish that we could never have imagined

possible. Acoustic tags are small pingers that

we surgically implant inside the fish so that every time they swim past a data logging

hydrophone (an acoustic receiver or “listening station”) the fishes ID is

recorded as well as time and date. Some tags

can even transmit swimming depth to the hydrophone. In

2000 I decided to study giant sea bass by implanting acoustic tags on a number of adult

fish and then setting up a large array of hydrophones to track their movements. Anacapa

Island was chosen as the study site since it was a well known site for catching trophy

giant sea bass when they were legal quarry; and an avid scuba diver, Kathy de-Wet Oleson,

had recently discovered a good aggregation site. With

generous funding from Tom Pfleger we were able to begin a program that would involve

completely surrounding Every

3 to 4 months we would go back into the field to dive and retrieve each hydrophone,

download the data and change the batteries before putting it back in the water. We soon learned that these fish behave much

differently than After

more than 5 years of data collection with our acoustic array we finally pulled all the

gear out of the water in November of 2006. During

that time span we amassed an incredible amount of data; we accumulated over 5 million

hydrophone “hits” from the giant sea bass we had tagged and I am just now

beginning to analyze the findings. One very

obvious pattern is that these spend the cold winter months in much deeper water; for

example, the average swimming depth of one fish was 59.7 feet in August of 2002 but 140.2

feet in December of the same year. We’ve

routinely tracked fish to depths greater than 350 feet in the winter. Also, four

individual fish traveled each year from Santa Catalina Island to Like

goliath grouper, giant sea bass have a diet that consists primarily of things they can

forage from the sea floor. Skate, rays,

flatfish (flounder, turbot, sand dabs etc.), lobster and mantis shrimp were all commonly

found in the stomachs of fish we caught for this study.

Occasionally we would find a barred sand bass or kelp bass, but these were

far and few between. Although

there seems to be anecdotal evidence that giant sea bass are slowly beginning to increase

in numbers, they have not responded to their protected status nearly as well as goliath

grouper have in Most

underwater hunters have no problem simply enjoying the sight of these big beautiful fish,

but it seems the temptation is too much for some. Sadly,

about once a year I am sent a photo of a giant sea bass swimming with a spear shaft either

protruding from the body or dragging it behind by the shooting line. Those of us who know better need to take every

opportunity to put pressure on the few who commit such acts to reduce the incidence of

unnecessary mortality. |

|

||

While the bsb may not be making the kind of comeback Floridians are seeing with the Goliath Grouper, there are definitely more fish now that they have become protected. One of the most exciting, and puckering, events we have while freediving in |

|||

Copyright © 2006 Terry Maas, BlueWater Freedivers |

|||